This study documented that TF-CBT provided directly to the child (in either the child-only or parent plus child condition) was superior in improving PTSD symptoms, while TF-CBT provided directly to the parent (in either the parent-only or the parent plus child condition) was superior in improving the child's depressive and behavior problems, as well as in improving positive parenting practices. (1996) randomly assigned 100 sexually abused children to standard community care or TF-CBT provided to the child only, the parent only or both. The strongest mediators of treatment response were parental support of the child and the child's sexual abuse-related attributions (Cohen and Mannarino, 2000).ĭeblinger et al. (Cohen and Mannarino, 1998b Cohen et al., in press).

Among treatment completers in the young adolescent study, TF-CBT was superior to NST in improving depression and social competence at the end of treatment, and in improving PTSD and dissociation at one-year follow-up. At one-year follow-up, the strongest predictor of positive response was parental support of the child (Cohen and Mannarino, 1998a, 1996b). The strongest mediator of treatment response other than type of treatment was parental emotional distress. These differences were maintained over a one-year follow-up (Cohen and Mannarino, 1997, 1996a). The preschool study demonstrated the superiority of TF-CBT in improving PTSD symptoms (including sexualized behaviors) and externalizing and internalizing behaviors. The nondirective supportive therapy consisted of play for younger children and child- or parent-directed supportive therapy for older children. Most of the TF-CBT treatment studies have consisted of 12 treatment sessions.Ĭohen and Mannarino conducted two parallel, randomized, controlled trials for 67 sexually abused preschoolers (3 to 6 years old) and 82 children and young adolescents (7 to 14 years old), comparing TF-CBT to nondirective supportive therapy (NST) (Cohen and Mannarino, 2000, 1998a, 1998b, 1997, 1996a, 1996b Cohen et al., in press). Several joint parent-child sessions are also included to enhance family communication about sexual abuse and other issues.

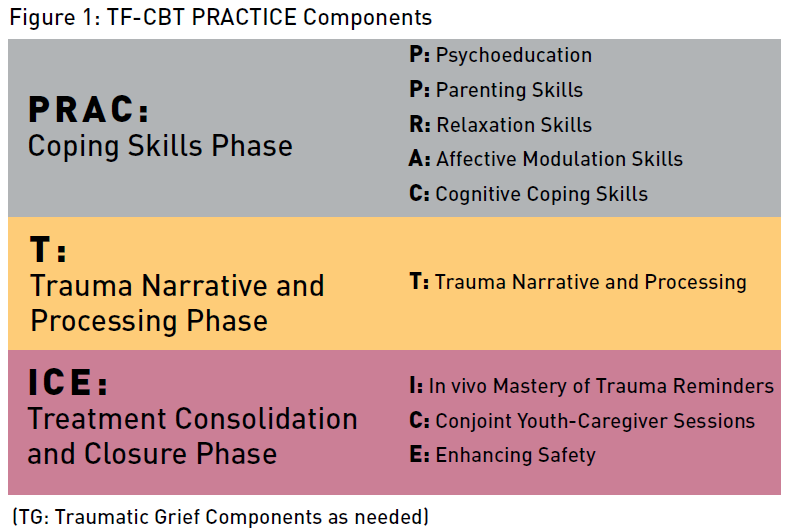

Parents are seen separately from their children for most of the treatment and receive interventions that parallel those provided to the child, along with parenting skills. The treatment also fits sexual abuse and other traumatic experiences into a broader context of children's lives so that their primary identity is not that of a victim.Ĭore components of TF-CBT are psychoeducation about child sexual abuse and PTSD affective modulation skills individualized stress-management skills an introduction to the cognitive triad (relationships between thoughts, feeling and behaviors) creating a trauma narrative (a gradual exposure intervention wherein children describe increasingly distressing details of their sexual abuse) cognitive processing safety skills and education about healthy sexuality and a parental treatment component. The therapy was developed to resolve posttraumatic stress disorder, and depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as to address underlying distortions about self-blame, safety, the trustworthiness of others, and the world. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy was jointly developed by two groups of researchers who have recently worked together to conduct multisite, treatment-outcome studies for sexually abused and otherwise traumatized children. This treatment model represents a synthesis of trauma-sensitive interventions and well-established CBT principles (Cohen et al., 2001 Deblinger and Heflin, 1996).

Most of the studies that have evaluated TF-CBT have been well designed. This article reviews the research that has examined treatments for sexually abused children and suggests future research priorities in this regard. Evidence is growing that trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is an effective treatment for sexually abused children, including those who have experienced multiple other traumatic events.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)